Electrolytes and Water: How They Work Together

Water and electrolytes exist together throughout the human body in a relationship defined by chemistry and physics. These two components, one a simple molecule, the other a group of charged minerals, interact in ways that shape the body's internal environment. Understanding this relationship requires looking at the properties of each and how they behave when combined.

The Chemical Relationship Between Water and Electrolytes

Water (H₂O) is a polar molecule, meaning it has a slightly positive end and a slightly negative end. This polarity makes water an excellent solvent for ionic compounds like electrolytes. When minerals such as sodium chloride enter water, the polar water molecules surround the ions, separating them from their crystalline structure. This process, called dissolution, is what allows electrolytes to exist in their charged form within bodily fluids.

The presence of dissolved electrolytes changes water's physical properties. Pure water and electrolyte solutions have different freezing points, boiling points, and conductivity. Electrolyte solutions can conduct electricity because the charged ions move freely within the liquid, carrying current from one point to another. Pure water, by contrast, is a poor conductor.

In biological systems, water serves as the medium in which electrolytes are suspended. Blood plasma is approximately 90% water, with the remaining portion comprising proteins, glucose, hormones, and electrolytes. Intracellular fluid similarly consists mostly of water containing dissolved minerals, proteins, and other molecules. Without water as a solvent, electrolytes would remain in solid crystalline forms, unable to participate in the body's chemistry.

The concentration of electrolytes in a solution is expressed in various units, including millimoles per litre (mmol/L) or milliequivalents per litre (mEq/L). These measurements describe how many particles are dissolved in a given volume of water. Different body compartments maintain different concentrations, creating what are called concentration gradients, differences in solute concentration between two areas.

Movement and Distribution Patterns

Water and electrolytes move throughout the body according to principles of chemistry and physics. Osmosis describes the movement of water across semi-permeable membranes, barriers that allow water to pass but restrict larger molecules or certain ions. Water moves from areas of lower solute concentration to areas of higher solute concentration, a passive process driven by concentration differences.

Cell membranes separate intracellular fluid from extracellular fluid. These membranes are selectively permeable, meaning different substances cross them at different rates. Water can pass through relatively freely via specialised channels called aquaporins. Electrolytes, being charged particles, generally require specific transport proteins or channels to cross membranes.

The movement of water in response to electrolyte concentrations occurs continuously. If the concentration of solutes outside a cell increases, water tends to move out of the cell. If extracellular solute concentration decreases, water tends to move into the cell. This principle, osmosis is a fundamental aspect of how body fluids are organised.

Active transport mechanisms also move electrolytes against concentration gradients. The sodium-potassium pump, for instance, is a protein found in cell membranes that moves sodium ions out of cells and potassium ions into cells, even though this goes against their natural diffusion direction. This process requires energy in the form of ATP (adenosine triphosphate) and maintains the characteristic electrolyte distribution pattern seen in living cells.

In the kidneys, water and electrolyte reabsorption occurs through epithelial cells lining the tubules. As filtrate passes through different segments of the nephron (the kidney's functional unit), water and various electrolytes are selectively reabsorbed or secreted. This process adjusts urine composition based on the body's current state. Concentrated urine contains less water relative to electrolytes; dilute urine contains more water.

Practical Contexts Where Water and Electrolytes Interact

Commercially available products demonstrate various approaches to combining water and electrolytes. Oral rehydration solutions, originally developed for clinical use, typically contain specific ratios of sodium, potassium, chloride, and glucose dissolved in water. The World Health Organization publishes a standard formulation containing 2.6 g sodium chloride, 2.9 g trisodium citrate dihydrate, 1.5 g potassium chloride, and 13.5 g glucose per litre of water.

Sports drinks represent another category, with formulations varying by brand and intended use. Some contain 10-25 mmol/L of sodium, others contain higher or lower amounts. Carbohydrate content also varies, from zero in some products to 6-8% in others. The osmolality, a measure of total solute concentration, differs between isotonic beverages (270-330 mOsm/kg, similar to body fluids), hypotonic beverages (lower osmolality), and hypertonic beverages (higher osmolality).

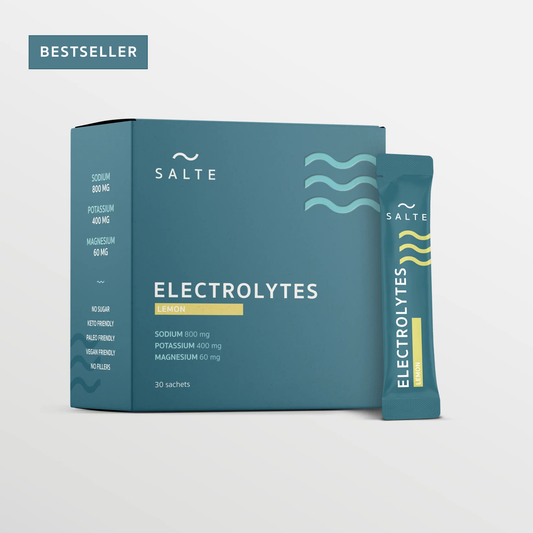

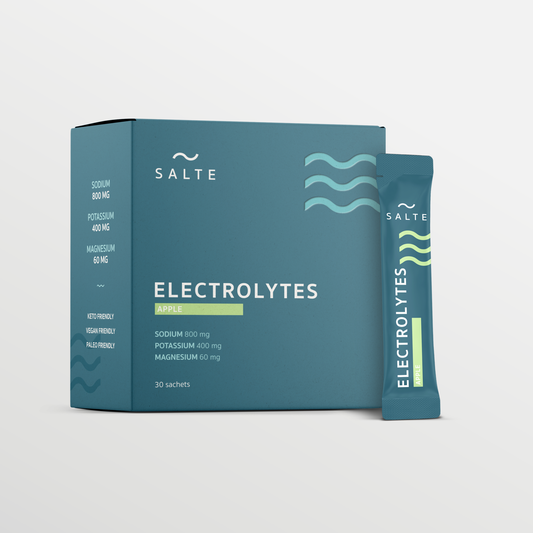

Electrolyte tablets and powders designed for mixing with water offer consumers control over concentration. A tablet dissolved in 500 ml of water creates a different concentration than the same tablet dissolved in 750 ml. The resulting solution's osmolality and taste depend on this dilution ratio.

Plain water contains minimal electrolytes unless sourced from mineral-rich springs or deliberately fortified. Tap water content varies by geography, with some regions having naturally higher mineral content than others. Distilled or deionised water contains essentially no electrolytes, representing the opposite end of the spectrum from concentrated electrolyte solutions.

The temperature of water affects how quickly electrolytes dissolve. Warm water generally dissolves solids faster than cold water due to increased molecular motion. This is why electrolyte powders often mix more readily in room-temperature or warm water than in refrigerated water.

The interaction between water and electrolytes is fundamentally about chemistry, charged particles dispersing through a polar solvent, creating solutions with distinct physical properties. This relationship exists in blood, sweat, urine, and every fluid compartment of the human body, as well as in the various beverages and products people consume daily.